To paint

by François-Marie Banier

This text was written by François-Marie Banier, on the occasion of the release of the exhibition catalog Fotos y pinturas which took place at Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires from the 17th of april until the 21th of may 2000.

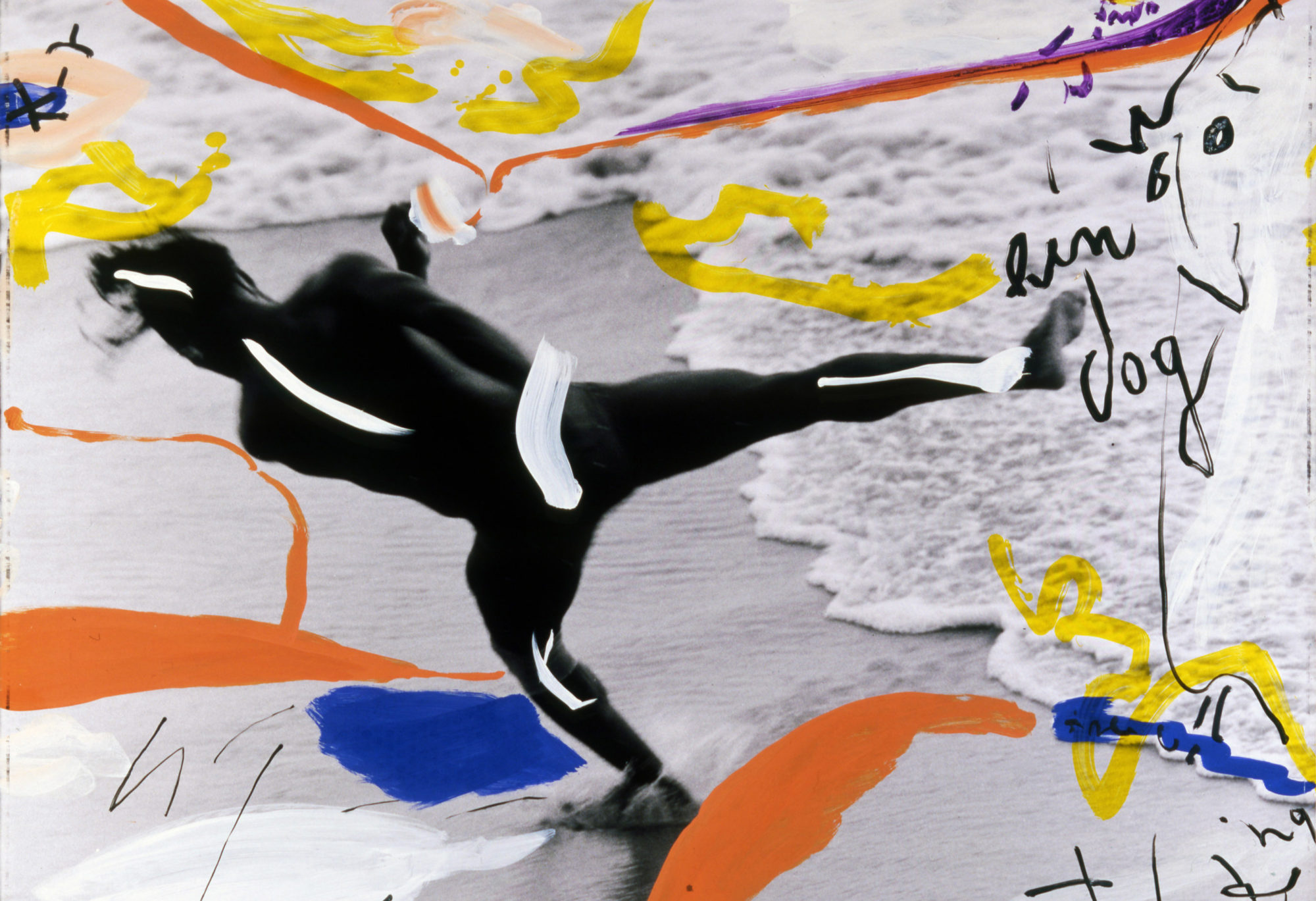

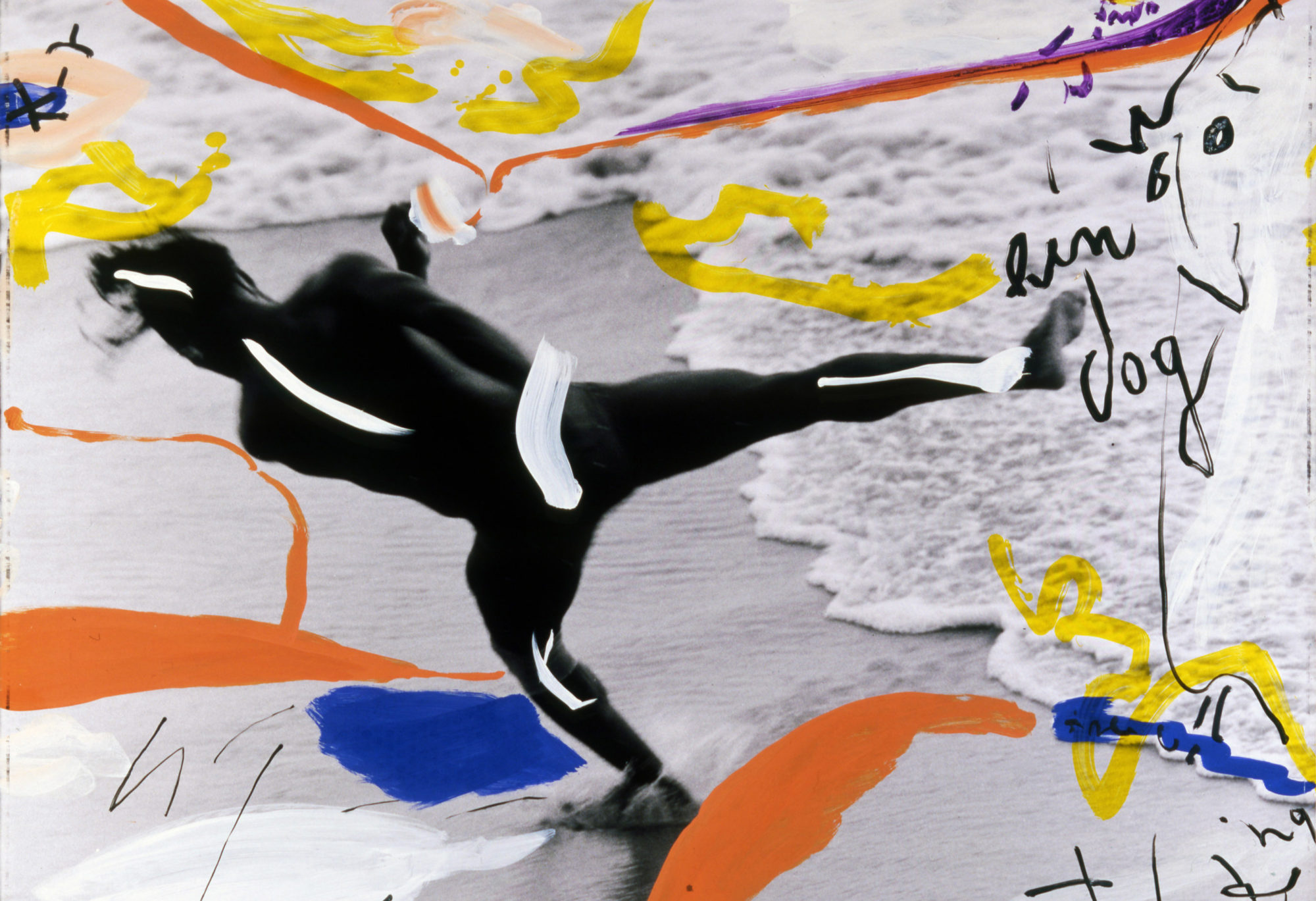

Photo: Le baigneur, 1999, by François-Marie Banier