Working notes

by Martin d'Orgeval

This text was written by Martin d'Orgeval, published by Steidl on the occasion of the release of the exhibition catalog Perdre la tête which took place at the Académie de France in Rome, Villa Medici, from the 26th of October 2005 until the 9th of January 2006.

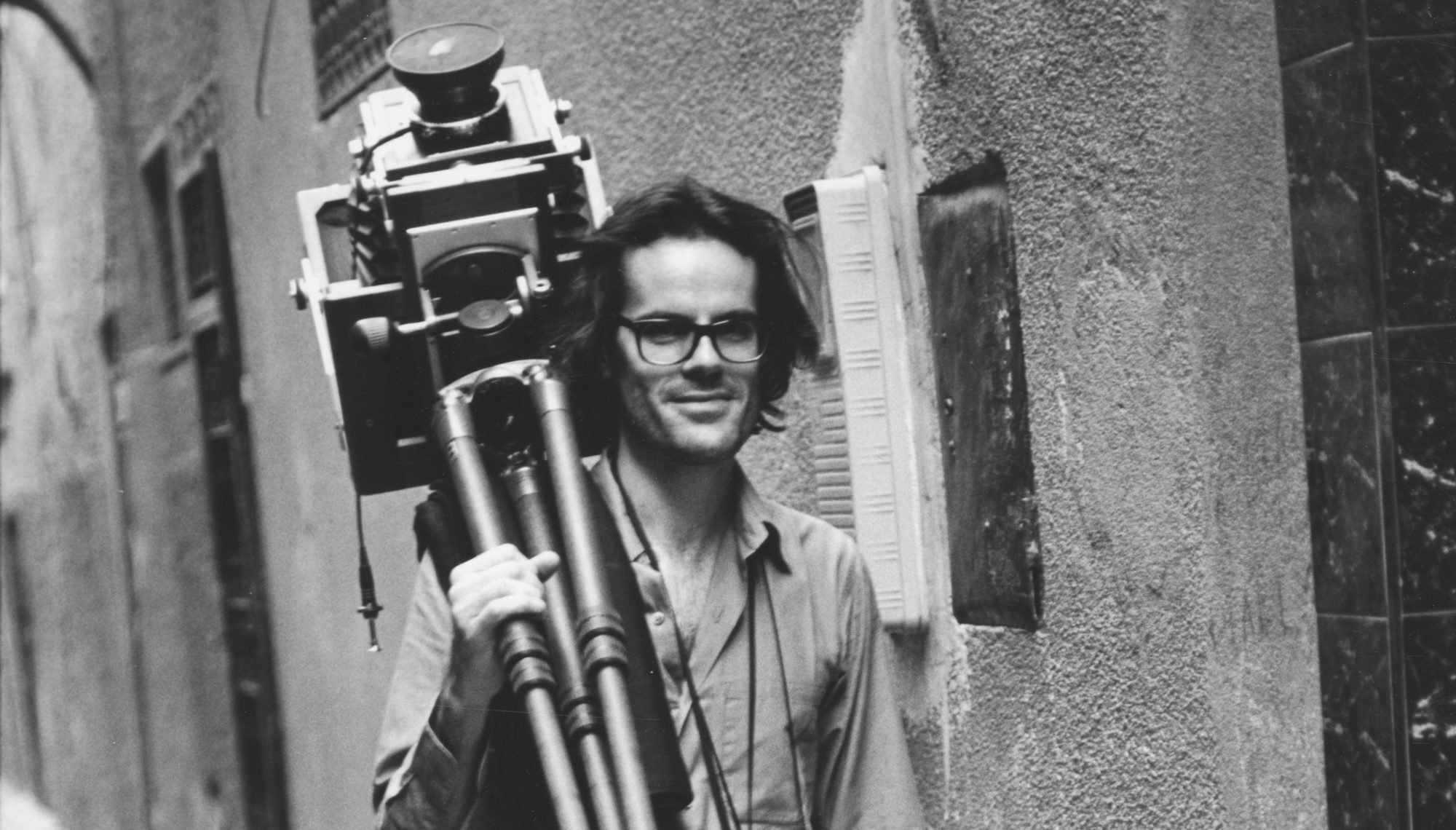

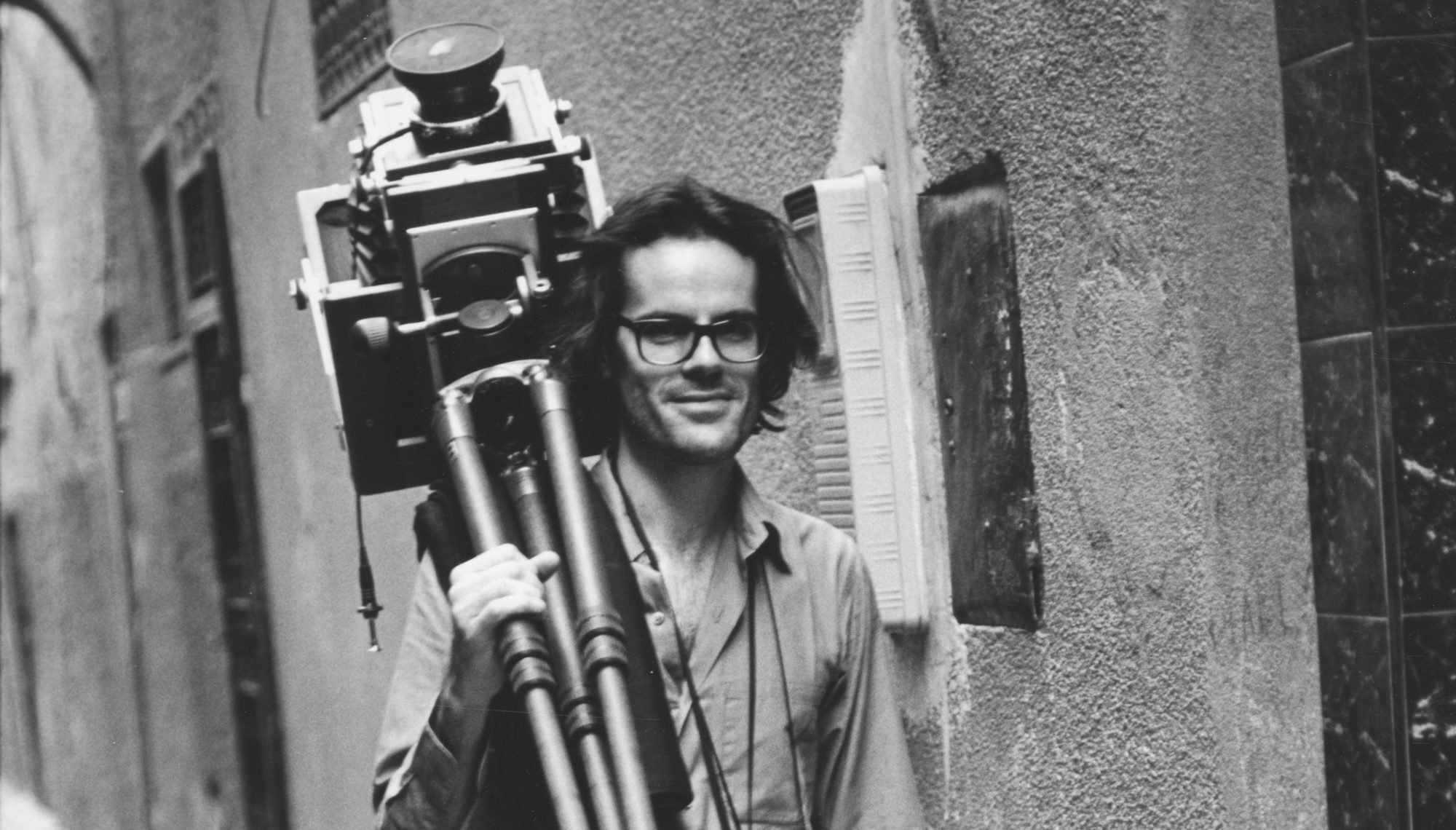

Photo: Martin D'orgeval by François-Marie Banier