The eternal other

by Martin d'Orgeval

This text was written by Martin d'Orgeval, published by Gallimard on the occasion of the release of the exhibition catalog François-Marie Banier which took place at Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris from the 26th of March until the 15th of June 2003.

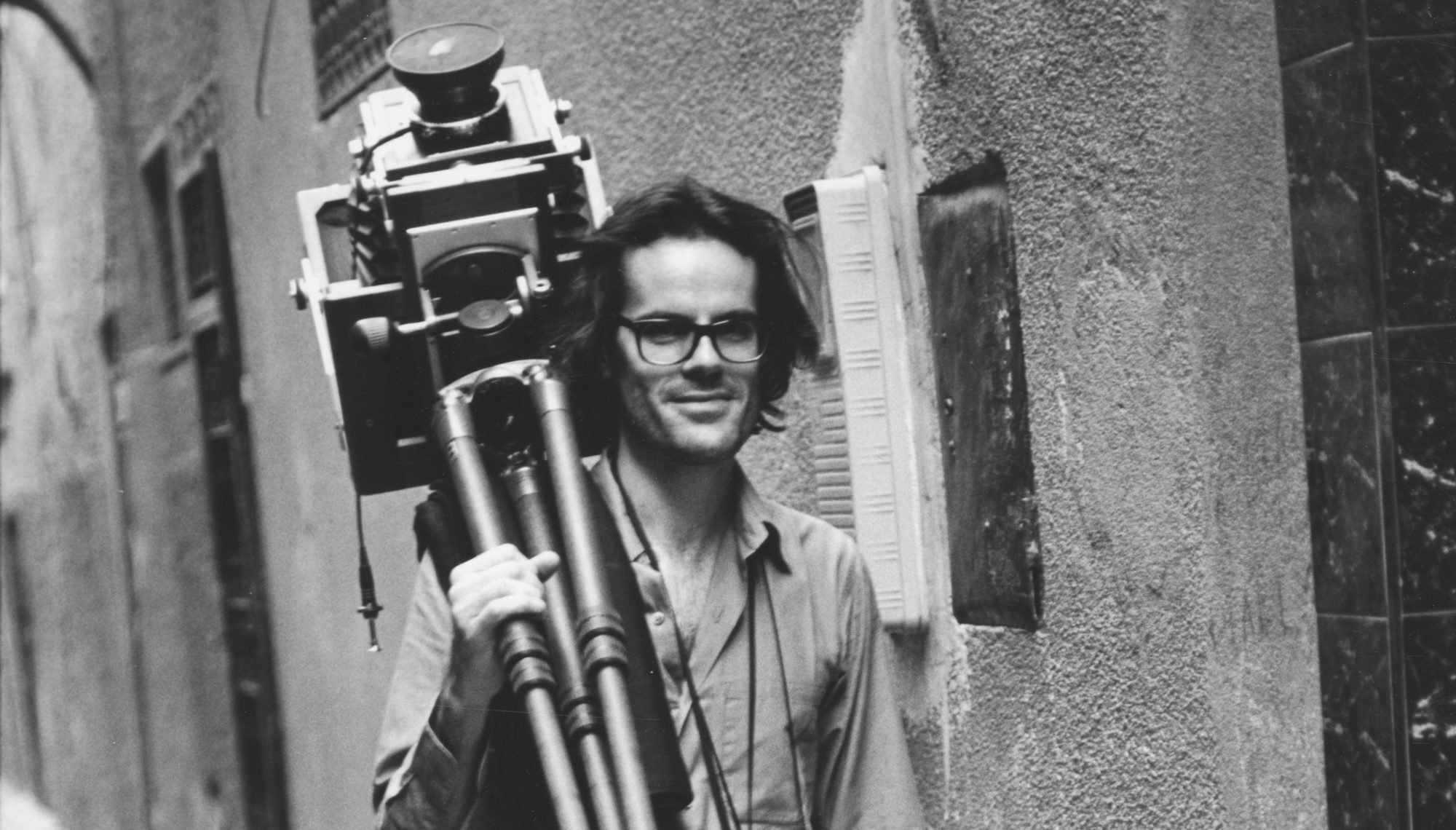

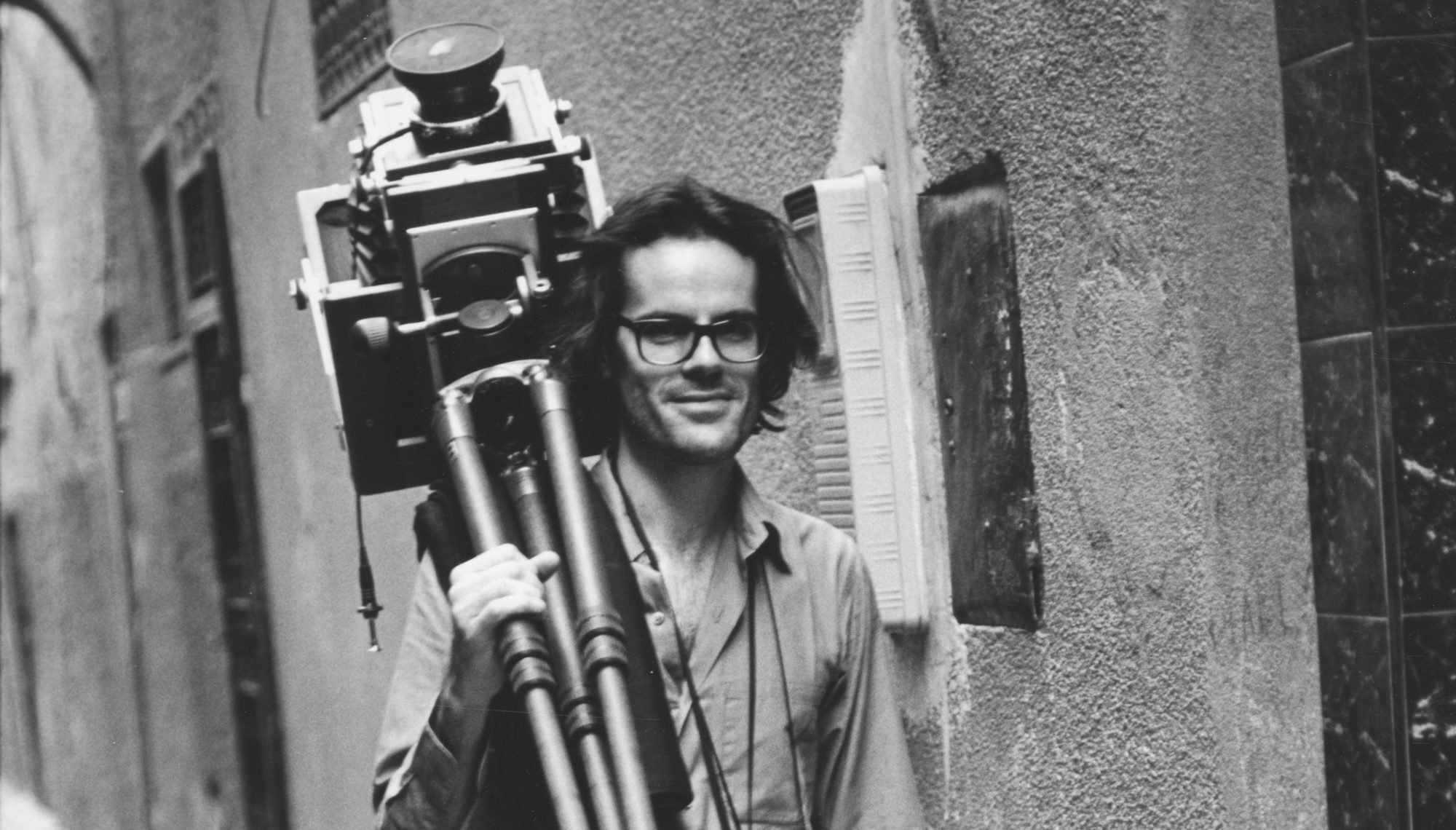

Photo: Martin D'orgeval by François-Marie Banier