The morning Banier and I went round his exhibition at the La Recoleta cultural centre in Buenos Aires, I felt the same sensation as I did the day I first met him, and that came back to me on the occasion of our subsequent conversations. As André Gide used to say, it is easy to break free; it is knowing how to be free that is hard. Looking at Banier’s paintings and photographs, I was sure that I had before me the work of a mind of the greatest originality, that originality particular to free souls. He is an artist who is absolutely alien to all the schematisations that end up forming new schools and new “isms”. If there is one thing that really doesn’t interest him, it is finishing up like all those “integrated” artists who throng the academies. On the contrary, Banier evinces a tension and a dynamism such that he could never be listed within the narrow margins of an aesthetic conception. His expressive force comes straight from the guts, without passing through the crucible of thought. He is a man with a faculty for forming sincere friendships from the first moment you meet him – which inclines you to think that this particular encounter had been waiting for you somewhere in the twists and turns of destiny. He has an extraordinary vitality and an overflowing joy which he communicates to those around him. Sometimes he gives the impression of being one of those clowns in whom, at certain moments, one glimpses an underlying melancholy.

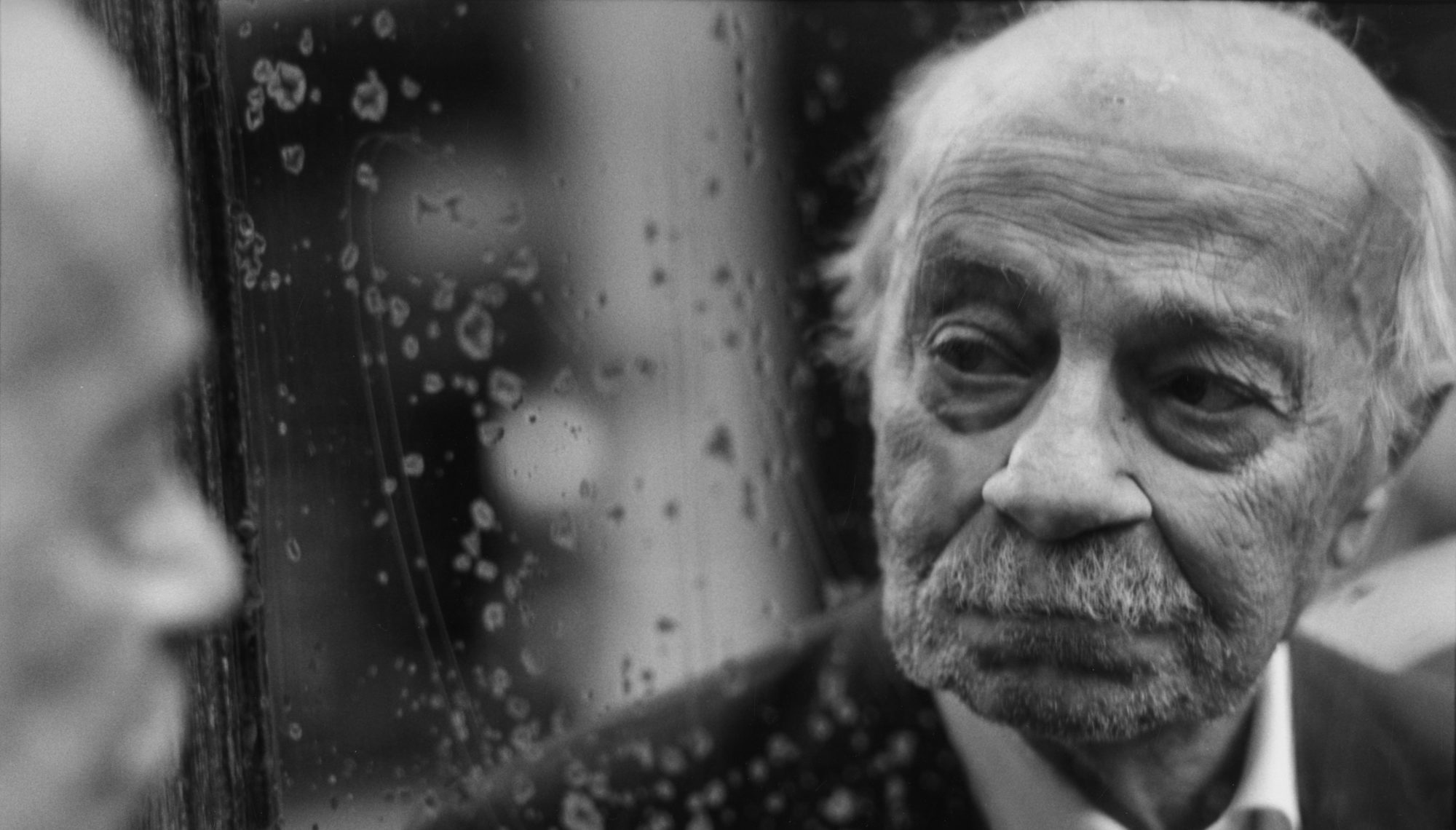

I would not hesitate to say that his need to paint, to write and, ultimately, to express himself, arises from an original lack which he hints at in his story of the young Balthazar. “I always wanted someone to love me, to be more than a child who is patted on the head and left, more than a surrogate son, more than a smart godson. Irreplaceable. I wanted to belong. To belong is to let go.” The memory of that heartbreak founds the compassionate gaze with which he paints those tortured beings for whom the meaning of existence is something to be struggled for every day. Whether they are anonymous figures or artists, musicians or renowned authors, I believe that what he tries to make manifest to our eyes is this common wound, the urgent, essential need to be loved and to belong, which lives in the hearts of all human beings. I even began to think that the running child seen in one of his superb photographs of Beckett sums up the mission that all great art is called on to perform, that of stopping time and recovering that moment when happiness slipped from our grasp.

It would be impossible to pick out the artists who have influenced him. When he releases the shutter, when he locks himself away in his studio or takes possession of a white page, the only thing that has preceded this instant is perhaps a dream, an impulse that carries him away, an imperative which simply has to be yielded to and obeyed. His paintings reflect that state of tension in which irreconcilable forces are astir in the depths of his soul. It would not be wrong to say that his whole being participates in his painting, like those children who throw themselves furiously on the colours and brushes. And indeed he could well be one those “enfants terribles” of Cocteau’s who refuse to be tamed.

This world full of sometimes devastating tensions brought to my mind a certain kind of cruelty, in Artaud’s sense of the word.

When we approach this sumptuous chaos, we are sucked in by the whirlwind of a world on the verge of collapse.

Banier is an unsatisfied, unreconciled spirit, drunk with a disturbing lucidity.